Table of contents:

I created my first Python package. It keeps track of what I am printing to the console in a log file along with the possibility to add a prefix to what I am printing.

💡 The Idea

As I coded multiple python programs that were running on a Raspberry Pi all day long, I always wanted to keep track of what my program was doing and when it was doing it. In order to do so, every time that my program received a piece of information or was actually doing something, I printed a text to the console explaining what was going on. This way, it was easy to debug after a problem occurred on some part of a project as I knew if the server received the information or not and if it took the correct actions based on it.

I was obviously not constantly watching the console feed all the time so I also needed to print the time before any statement. Therefore, I was easily able to debug what went wrong at a certain time based on the console feed.

I was still facing two issues:

- When a bug would cause my python program to crash, I would loose all the console feed containing the precious debugging data.

- When I would restart my program, I would not be able to get back the previous console feed. I only had the currently running console feed and no history of the previous runs.

This is when I had the idea of creating a python package which could print out statements directly with a prefix containing the current date and time. The package could also save the console feed inside a log file. I would then be able to see the console feed after closing the program and access any past run output.

💽 The Old Way

Before the creation of this package, I was printing out statements this way:

1

2

3

4

5

import time # one time only

hour = time.strftime("%d.%m %H:%M:%S | ")

statement = "-> Data sent successfully"

print(hour + statement)

Every time I needed to print out something I was creating a prefix using the strftime method of the time package (line 3). After that I concatenated the prefix with the statement before printing the result (line 5).

Doing it in that way let me to have the prefix before the statement but didn’t store anything in a log file.

🛠 The Creation

Introduction

Although I coded a lot in Python, I had never wrote a package or anything close to it. I took it like a good opportunity to learn a new skill in this language. I wanted my package to be easily installed on any computer with a pip command like the other packages I installed in the past. This is where I stared.

PyPi

I first needed to understand where and how to make my future package available to anyone using the pip command. That led me to search where the different python packages are stored. I found out that they were stored on PyPi, the Python Package Index.

Once I knew that, I searched a way to publish a package on PyPi. I found this tutorial on Medium wrote by joelbarmettlerUZH.

It was really helpful and it covered everything from the point where you finished writing your code to the pip install your_package command.

I read this article so that I knew how to write my code in order to make it easier to publish on PyPi once I would finish coding my package.

Coding

Now that I knew how to write my package in a way that would make it accessible to anyone, I needed to actually code it. I started my reflection by asking myself which categories of statements I wanted my package to be able to display. I found 3 main categories:

- An information

- A warning

- An error

I did some research about log files in python and this is where I found the logging package. This discovery made my work a lot simpler because it almost perfectly matched my goal of keeping track of what I was printing inside a log file. I learned a bit about how to use this package and ran some tests. I was pretty satisfied about it and I started implementing it inside my own package. It wasn’t an issue to use it inside my package because it is part of the Python Standard Library. That meant that I didn’t need to mess with requirements or anything like that because (almost) everyone already had the logging package installed on their machines.

I coded the main methods of my package which were:

- The initialisation method,

init - The exit method,

exit - The info method,

info - The warning method,

warn - The error method,

err - I also added a new category which was the debug method,

debug

(I am not going to describe each method here but you can read more about them in the documentation of the project that you can find on the project’s GitHub repository.)

Customisation

I wanted my package to be as customizable as possible. In order to let the users customise the package, I created the following methods:

- Customizing the printing prefix the way they want,

custom_PRINTPREFIXFORMAT - Customizing the logging prefix the way they want,

custom_LOGFORMAT - Disabling or enabling the printing on the console,

disable_PRINTOUTenable_PRINTOUT - Disabling or enabling the record of the statements on a log file,

disable_LOGFILEenable_LOGFILE - Modifying the directory where the log files are saved,

custom_LOGPATH

(I am not going to describe each method here but you can read more about them in the documentation of the project that you can find on the project’s GitHub repository.)

Documentation

At this time the coding part was pretty much done but I still needed to write an understandable documentation for futur users. I didn’t want something perfect, just something useful and that was capable of explaining how my package worked and how to use it. I stared by writing some comments inside my code in order to explain different parts of each method. After that I wrote a docstring for each method describing its purpose and its use. Then I wrote some basic examples of uses and explained how to initialise and exit the package. I also styled everything using Markdown. That way, the documentation is nicely displayed in Visual Studio Code or any other text editor which supports Markdown documentation rendering.

After the documentation was written in the code, I still needed to write a README.md file for the GitHub repository. I wrote it pretty fast just including:

- A description of my package

- The features it brings

- A detailed documentation

- Example.s for each method

The name

I had a really cool name inside my head since the beginning of the project. That name was BetterPrint.

It was a good representation of what I was trying to achieve but unfortunately, it was already taken by another package.

I could take another name for the package installation and still be able to import my module with the name BetterPrint but I was not really convinced by this idea.

I don’t really like when other packages do that. For example the well known computer vision package called OpenCV needs to be install with the following command: pip install opencv-python. However it needs to be imported inside a python script like this: import opencv.

It is a small detail but I like the fact that when you look at someone’s code and there’s a package you don’t have, you can simply run the pip install package_name command in order to get it.

This is why I wrote an email to the person who has the package called BetterPrint in order to see with him if he was ok to change his package name so I could use his. I thought that he would say yes because his package has not been updated for years but his answer was negative 😥.

At this time I needed to find another name to my package. There were many candidates such as:

- SimplePrint

- EasyPrint

- LogPrint

- BestPrint

- …

I was not fully satisfied by any of this names. At some point I realized that I could just invert the Better and the Print order in the name which, thankfully, was not already taken! That gave me the final name which is PrintBetter. It was the most convincing name to me so I went with that one.

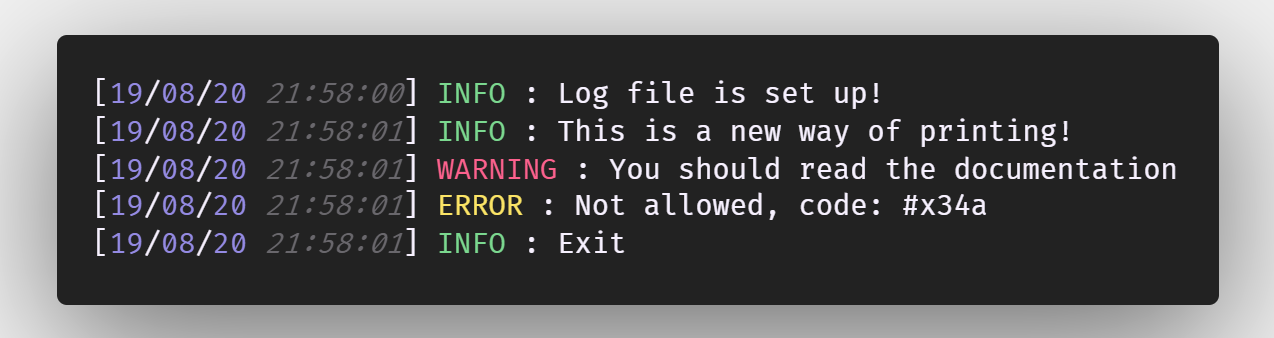

🎉 The New Way

When I finished my package, I was pretty satisfied with the final result. My initial issue is fixed and I am definitely going to use this package in a large number of futur projects. This is the new way of printing things to the console:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

import printbetter as pb

pb.init() # initializes

pb.info("information")

pb.debug("variable debug")

pb.warn("warning")

pb.err("error")

The first line is where my package is imported in my python script. On the third line I am initializing the module with the default parameters (no additional information). After that comes a series of method calls which each has their own purpose. They already have been described in the Coding paragraph. At the end, at line 10, I am terminating the module.

📤 Publishing

Even thought I read all the explanations in the article (see PyPi paragraph) about publishing my package to PyPi I ran into multiple difficulties durning this process.

I needed to create many different files in order to publish my packages:

- LICENCE.txt

- MANIFEST

- description.rst

- setup.cfg

- setup.py

I was a bit confused when I wrote each of these files. The LICENCE.txt was the easiest file because I just choose one of the basic licenses for my package and everything ran smoothly with it. The MANIFEST was automatically generated so it was not an issue either. The description.rst file was slightly more difficult but nothing crazy. It is the file used by PyPi to display a small description of the project on their website. It used the reStructuredText file formatting which is a bit like Markdown but using a different syntax. The setup.cfg was a very small file so it was not hard to setup.

The only file which gave me lots of issues was the setup.py file. I needed to modify it many times and my package became a mess because every time that I made a change to the file I needed to release my package and then upload it to PyPi in order to see if my changes worked. This is why there was six releases of my package till it was finally fully published like I wanted.

📄 Conclusion

In the end, I am really happy with what I have done with this package. I use it in a lot of projects now as it is pretty helpful. I am also happy about the documentation that I wrote because even if I knew that probably no one will ever read it or even use my package I wanted to build it as if people would. This gave me the full experience behind building and publishing a python package and I learned a lot thought this process. The final result is clean enough for me so maybe I will update it in the futur if I have any additional ideas but not for the moment.

This was a fun and useful project and I would recommend to any python developer to do the same thing if they have any package idea as it is another side of coding we do not always think of. We often use lots of packages at the beginning of any python file but this was the first time I really saw the “behind the scenes” of those and it was very interesting.